On 15 March, the Global Partnership on Drug Policies and Development (GPDPD) published International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy. The document was produced alongside The International Centre on Human Rights and Drug Policy, the UN development programme, UNAIDS and the World Health Organisation.

The guidelines “are a reference tool for policy-makers, diplomats, lawyers and civil society organisations working to ensure human rights compliance in drug policy”. They aim to address the gap created by a “lack of clarity as to what human rights law requires of States in the context of drug control law, policy, and practice”.

They do not invent new rights. They apply existing human rights law to the legal and policy context of drug control in order to maximise human rights protections, including in the interpretation and implementation of the drug control conventions.

The report is therefore based on the five foundational human rights principles:

- the right to human dignity;

- the universality and interdependence of rights;

- the right to equality and freedom from discrimination;

- the right to meaningful participation in public life;

- the right to hold the State accountable and the right to an effective remedy when human rights are undermined.

Human rights are, of course, often ignored by UN member states. After all, the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs itself emphasised a concern for the health and welfare of mankind. Its ostensible purpose was to protect people from the “harms” of certain substances. But it was also meant to make sure that these substances were available for the relief of people’s pain and suffering.

As Julie Hannah, Director of the International Centre on Human Rights and Drug Policy, recognises in her video introduction to the report, the consideration of and respect for human rights of individuals and communities “has not always been the norm”, to put it lightly. It recognises that prohibition and punitive drug policies have “led to serious human rights violations, such as extrajudicial killings and the systematic discrimination of certain ethnic or social groups”.

“A drug policy that is not checked against human rights standards may increase the possibility for such violations to occur,” she says.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has named some key areas to pay attention to: the right to health; protection of children; indigenous people’s rights; non-discrimination; and rights related to criminal justice.

Around the world, legally-binding obligations often go unmet – including access to essential medicines, which was supposedly a key objective of the 1961 Convention. According to WHO, 80% of the world’s population has limited or no access to essential pain medicine.

Britain and the foundation of human rights principles

Guidelines are of course merely recommendations that can be ignored. However, where a clear legal standard already exists, the report uses the word “shall” instead of “should”.

For example, in accordance to the right to equality and non-discrimination, the report says States shall:

1) Take all appropriate measures to prevent, identify, and remedy unjust discrimination in drug laws, policies, and practices on any prohibited grounds, including drug dependence.

(2) Provide equal and effective protection against such discrimination, ensuring that particularly marginalised or vulnerable groups can effectively exercise and realise their human rights.

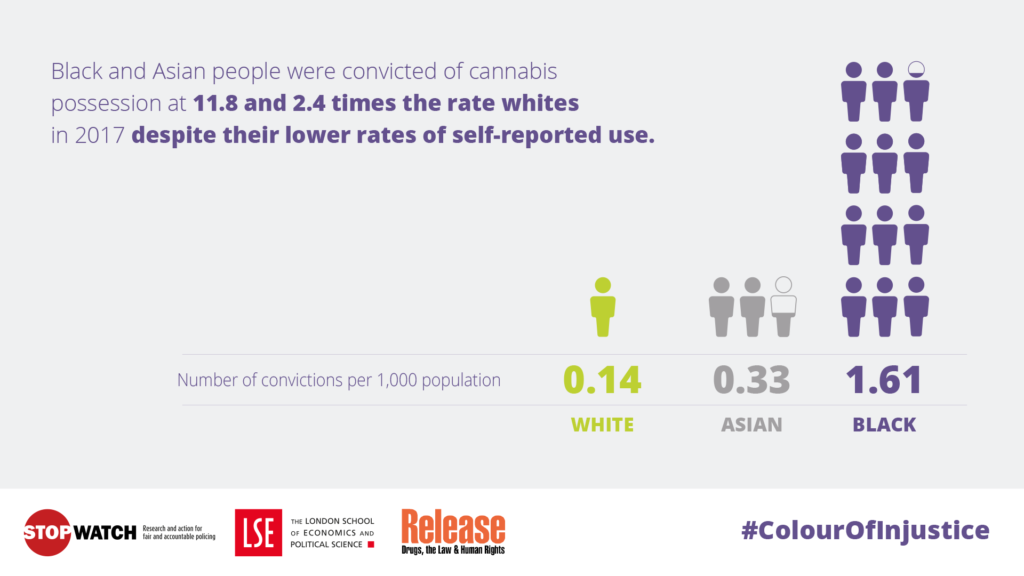

Clearly Britain is in violation of this given that drug law enforcement here massively discriminates against black people. See the report by StopWatch, Release and LSE, The Colour of Injustice: ‘Race’, drugs and law enforcement in England and Wales.

Going back to point 1, clearly people are denied the right to human dignity in all manner of ways in the UK – homelessness, deportations, police brutality, etc, etc. With regards to drugs, those of us who need cannabis to medicate are of course denied this legally and therefore denied the right to dignity.

The right to participate in public life is of course particularly relevant for activists. The report says:

This includes the right to meaningful participation in the design, implementation, and assessment of drug laws, policies, and practices, particularly by those directly affected. In accordance with this right, States should:

(1) Remove legal barriers that unreasonably restrict or prevent the participation of affected individuals and communities in the design, implementation, and assessment of drug laws, policies, and practices.

(2) Adopt and implement legislative and other measures, including institutional arrangements and mechanisms, to facilitate the participation of affected individuals and groups in the design, implementation, and assessment of drug laws, policies, and practices.

(3) Remove laws depriving people of the right to vote as a consequence of drug convictions.

Do we feel, especially as people who are directly affected, that we have the full right to participate in these ways in Britain? Prohibition at least severely limits it. In Britain the public certainly has had no say in the design and implementation of any policy. Campaign groups get a hearing, occasionally in parliament, sometimes in the media, but are rarely really listened to, let alone consulted and empowered to act on drug law. If that were the case the law change last year would have resulted in more than the four prescriptions that have since been handled out. At best, a small minority are allowed to participate in a game of divide and rule. No, most of us have to break the law to survive. Our meaningful participation in Britain is illegal.

To point 5:

“Every State has the obligation to respect and protect the human rights of all persons within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction. Everyone has the right to request and receive information about how States have discharged their human rights obligations in the context of drug policy. Everyone has the right to an effective remedy in the event of actions and omissions that undermine or jeopardise their human rights, including where these actions or omissions relate to drug policy.”

The right to effective remedy includes ensuring

“that independent and transparent legal mechanisms and procedures are available, accessible, and affordable for individuals and groups to make formal complaints about alleged human rights violations in the context of drug control laws, policies, and practices”.

Given that legal aid has all but been abolished in Britain since 2010, this is another right that is clearly denied.

Those following cannabis culture closely will be aware that this right to privacy is what was won in Spain by the operation of over 1,000 cannabis social club associations in Barcelona. This initiative has now spread across Europe, South America and South Africa.

Obligations arising from human rights standards

Section two of the document lists the obligations arising from human rights standards.

Point 1 is “the right to the highest attainable standard of health”, which again we are currently denied

This includes the recommendation that States should

“address the social and economic determinants that support or hinder positive health outcomes related to drug use, including stigma and discrimination of various kinds, such as against people who use drugs”.

Drug users have been stigmatised by successive governments and the media for decades in this country. Britain fails again, as it does on economic accessibility.

States should therefore

“repeal, amend, or discontinue laws, policies, and practices that inhibit access to controlled substances for medical purposes and to health goods, services, and facilities for the prevention of harmful drug use, harm reduction among those who use drugs, and drug dependence treatment“.

In addition, States “may” (used when there are already existing “permissive norms”)

“utilise the available flexibilities in the UN drug control conventions to decriminalise the possession, purchase, or cultivation of controlled substances for personal consumption”.

Clearly this is applicable to cannabis.

Point 1.1 and 1.2 recommend the right to harm reduction and drug dependency treatment “on a voluntary basis” and 1.3 recommends “access to controlled substances as medicines”.

States should therefore

“take legal and administrative steps to ensure the adequate availability, accessibility, and affordability of controlled medicines”;

and

“Consider reviewing the 1961 and 1971 drug control conventions’ schedules of substances under international control in light of recent scientific evidence, and prioritise exploring the medical benefits of controlled substances in accordance with the World Health Organization’s scheduling recommendations.”

Point 2.2 is “the right to benefit from scientific progress and its applications”. Little chance of that happening while prohibition prevents research on cannabis!

“Everyone has the right to privacy, including people who use drugs,” says point 9.

Those who are close to cannabis culture know that the right to privacy played an important role in the founding of 1,000 cannabis clubs in Barcelona. The practice has spread around Europe and Latin America.

States “may”, it says “utilise the available flexibilities in the UN drug control conventions to decriminalise the possession, purchase, or cultivation [our emphasis] of controlled substances for personal consumption”.

Does “purchase, or cultivation” point to support for legalisation and regulation?

So… will the UK state do any of this now that the UN has adopted a position of recommending “decriminalisation of drug possession and use” – or will it continue to suppress our human rights?

We have covered here the main points affecting the legalisation movement in Britain. To see what else is in the report regarding drug policy and human rights, read the full report here.