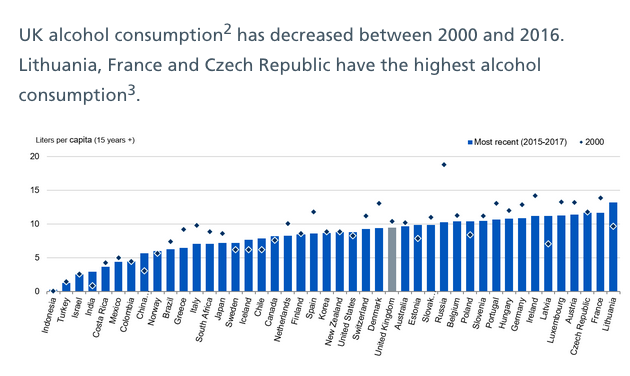

The proportion of people drinking to excess in England has fallen slightly in the last year, largely because young adults – including the oft-maligned millenials – continue to turn away from alcohol. While rises in alcohol-related deaths and hospital admissions are growing in absolute terms – roughly in line with population growth – broadly stable relative figures show that progress is stagnant, although consumption has fallen over the past 15 years. Someone is admitted to hospital every 30 seconds where drinking is a factor.

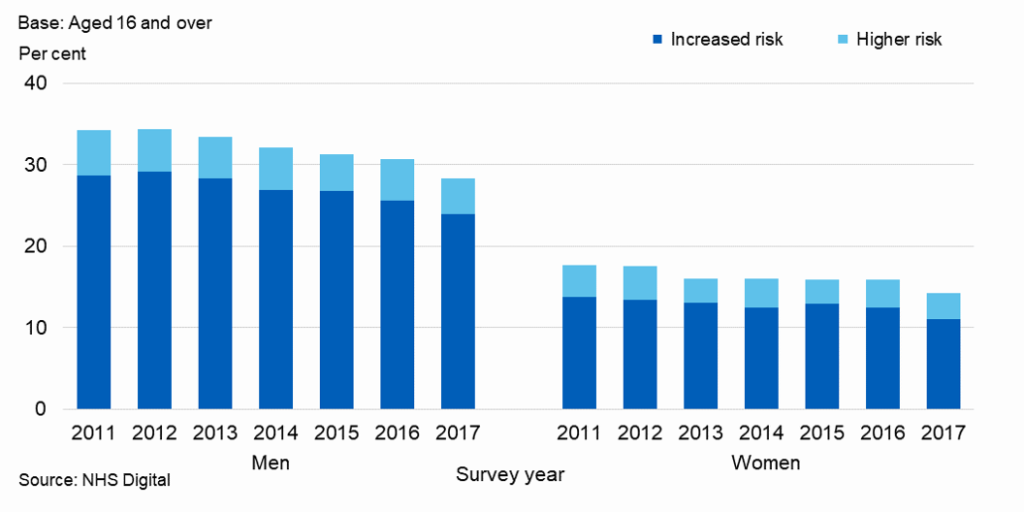

Overall, according to NHS Digital, 21% of people aged 16 and over in England drink more than the 14 units a week recommended by the UK’s four chief medical officers, a slight fall on the previous year, continuing a trend of slight falls over the past six years – 6% among men and 4% among women since 2011.

Men and women over 16 usually drinking at increased or higher risk of harm decreased between 2011 and 2017 (from 34% to 28% of men, and from 18% to 14% of women), both falling slightly on 2016.

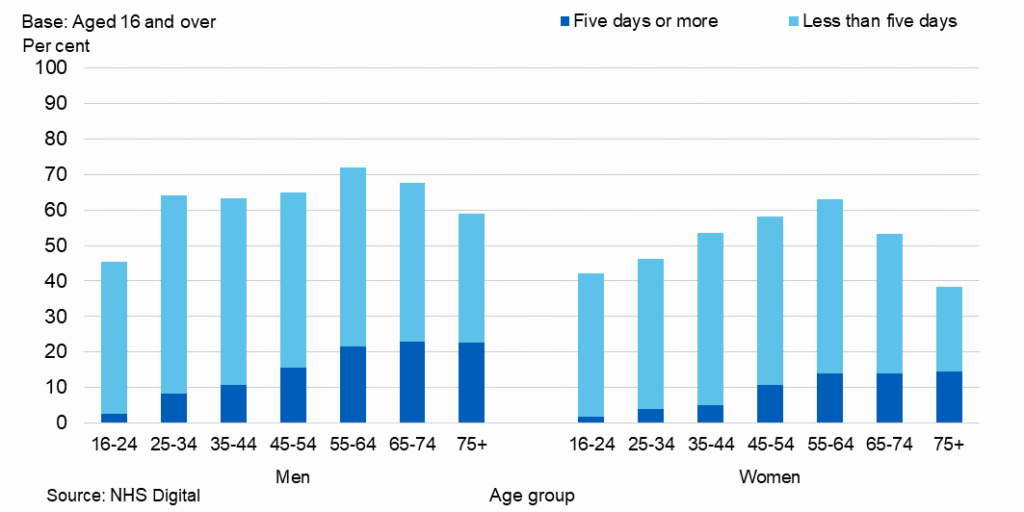

Richer, older men are the most likely to drink to excess. The proportion of men and women usually drinking over 14 units in a week varied across age groups and was most common among men and women aged 55 to 64 (36% and 20% respectively). Proportions drinking at these levels then declined among both sexes from the age of 65.

The table below shows that 16-24 year olds are by far England’s most responsible drinkers. Poorer households also drink less, although of course alcohol specific death remained higher in more deprived areas where there were 30.1 deaths per 100,000 for men and 13.5 for women

The proportion of adults usually drinking at increased or higher risk of harm was highest in higher income households for both men and women, with 35% of men and 19% of women.

In the lowest income households, 20% of men and 12% of women drink at increased or higher risk of harm. When looking just at higher risk, there were no differences by income.

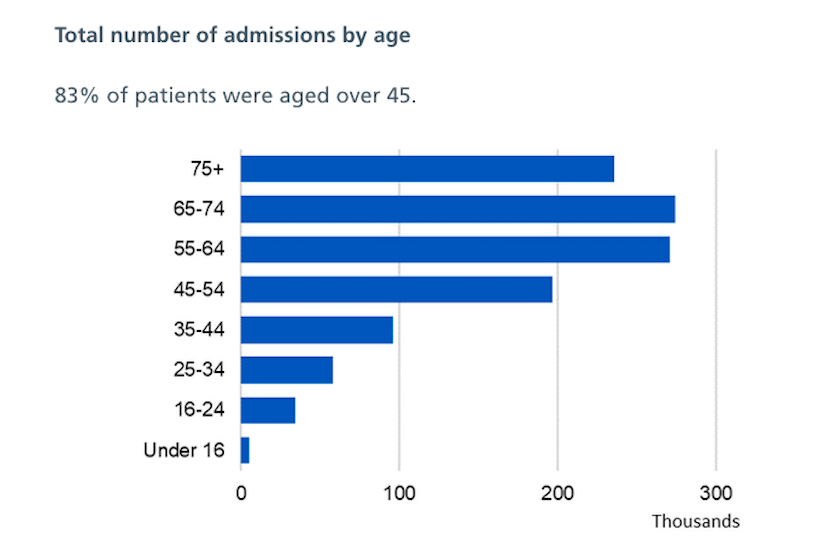

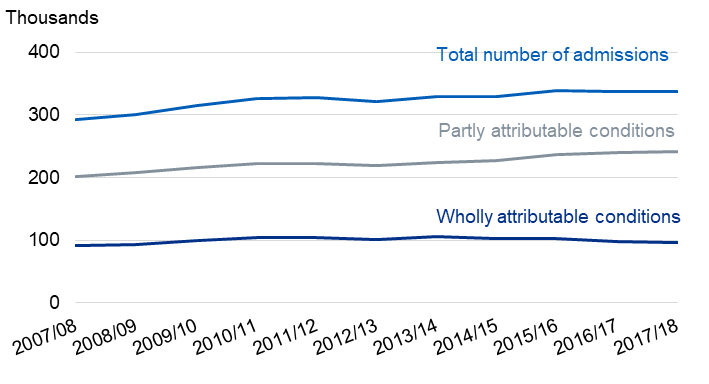

The number of people admitted to hospital for a cause directly related to alcohol was 338,000, a figure that rises to 1.2 million when taking the broadest possible measure for alcohol admissions (where alcohol might be a contributing cause to a condition but not the primary one). That’s one in every 14 patients and up from 100,000 in just a year. However, the 338,000, while up absolutely by 15% over the decade, represents 2.1% of overall admissions in 2017/18 compared to 2.3% in 2007/08.

In terms of deaths directly caused by alcohol in 2017 the number was 5,800, up 6% from 2016 and 16% higher than in 2007, with 80% of those deaths being from alcohol-related liver disease.

The number of people treated for problematic drinking in 2017/18 was 76,000, 6% lower than 2016/17.

The alcohol-specific age-standardised death rates per 100,000 population were 15.0 for males in 2017 which is over twice the rate for females (7.4). The relative rates – ie proportions of the population – for both men and women has “remained broadly similar since 2007”, said the report.

The rise in alcohol-related hospital admissions in recent years should be understood in the context of an ageing population that drank at much higher levels and is now reaping the consequences. This is also the demographic who are more likely to drink over 14 units a week.

The rise in alcohol-related admissions may yet rise further but if the decline in drinking among the under-40s continues then, presumably, admissions must peak eventually and then there will be a decline.

While the media’s focus on absolute instead of relative growth in figures is somewhat disingenuous, there is still plenty of cause for concern. Low relative growth still represents little or no progress in tackling excessive drinking overall over the past decade, with the lower figures for younger people suggesting that older drinkers must be drinking more.

Higher awareness of the dangers related to drinking is clearly leading to young people consciously adopting healthier lifestyles, looking for healthier alternatives and leading society by example.

Katherine Severi, chief executive of the Institute of Alcohol Studies think tank, said that it was still “worrying that one in five adults are drinking at levels that increase their risk of health problems such as cancer, liver cirrhosis and heart disease. This puts a strain on our NHS and reduces our economic productivity, making us an unhealthy nation all round.”

Figures showing that poorer households drink less than affluent ones “demolish the stereotypes linked to alcohol problems, which aren’t confined to a small minority of so-called irresponsible drinkers. Affluent, well-educated groups are drinking the most.”