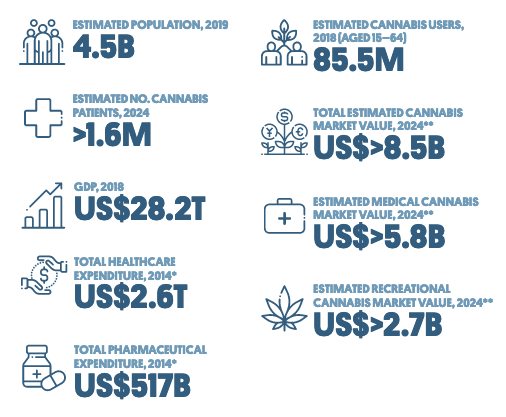

Following its African Cannabis Report in March, Prohibition Partners has now published a report into Asia, a market it calculates could be worth upwards of $8.5bn by 2024 if both medical and recreational cannabis are legalised across a number of countries. The figure for medicinal alone is $5.4bn, which could quadruple by 2027.

The report anticipates that in the next five years, Asia will cast aside decades-old draconian prohibition policies – which has included the death penalty for minor drugs misdemeanors – following on from international trends. At the end of 2018, Thailand’s parliament voted almost unanimously to legalise medical cannabis, while Malaysia indicated in February this year that it is considering following suit, while Singapore also declared its intention to allow the legal sale and use of pharmaceutical products containing cannabinoids (CBD). Under pressure from the domestic Great Legalisation Movement, the government of India is in early discussions about whether to legalise the medicinal cannabis market. In 2018, Sri Lanka launched its first plantation to produce cannabis for medical use locally and also for export to the US.

Asia’s legal systems are a legacy of British colonialism and then US hegemony, with pressure being applied on countries to adhere to international treaties such as the International Opium Convention, which was revised in 1927 to include cannabis.

“Shortly after,” the report explains, “a wave of countries in Asia began to take a zero-tolerance approach to cannabis and other substances. Indonesia first banned cannabis in 1927 while under Dutch colonial rule; Thailand criminalised it in 1935; and other nations, including Japan and South Korea, followed with their own Cannabis Control Acts. As the global war on drugs intensified, countries felt pressure to sign the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, and the US provided legislative and field support throughout the 1960s and 1970s to prevent the cultivation of cannabis in the region, most notably in Vietnam and Afghanistan. In more recent decades, crop substitution schemes have been rolled out in countries such as Pakistan and Afghanistan to encourage local economic alternatives to cannabis farming.

With conservative attitudes towards drugs becoming the norm, some countries, for example, South Korea, Japan and China, have recently, in the face of North American legalisation, reminded citizens not to indulge in cannabis consumption even if they are in a country where cannabis is legal. However, with investors looking for global outlets, it is unlikely that countries will resist forthcoming economic opportunities.

As the report notes, cannabis use is deeply rooted in some of the region’s ancient medical practices. Ayurvedic medicine in India was used 3,000 years ago to treat a range of conditions from blood pressure to skin conditions and glaucoma, while in China cannabis seeds were recorded in ancient medical texts “as long as 2,000 years ago”. This legacy is perhaps why, while patenting hybrids is big business in the West, in Asia it is forbidden to patent living organisms. The cannabis plant, thought to be one of the earliest plants cultivated in the region, grows widely across Asia and is indigenous to Central and South Asia.

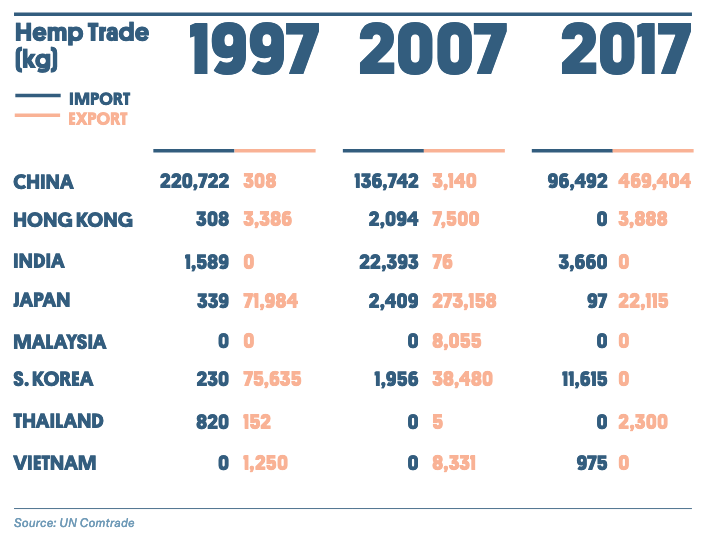

China has already established global dominance in hemp, accounting for nearly half of the world’s supply, worth an estimated annual $1.2bn. Between 2007 and 2017 its hemp exports grew from 3,140kg to 469,404kg. The number of new specially developed high-CBD cultivars in China is now also on the rise. Asia is expected to become a major player in industrial cannabis and in hemp-derived CBD.

India, Nepal, South Korea and Thailand also grow hemp on a large-scale commercially and India has a growing number of agricultural training programmes and practices across farming communities that are committed to spreading knowledge about hemp.

Although consumption of cannabis may remain at odds with religious and cultural beliefs in some Asian countries, the use of hemp for non-consumable items such as fibre, textiles, rope and netting indicates the potential for a booming industry, which could provide ancillary jobs and taxes throughout the region. South Korea has already developed an interest in hempseed as a substitute for fish protein after its citizens became wary of eating fish after the 2011 Fukushima reactor disaster in Japan. It has also taken steps to allow imports of cannabis-derived medicines. Japan legalised CBD oil in 2018 and is currently piloting hemp production.

While the annual cannabis consumption rate in Asia is only 2%, that still amounts – given that Asia is the most populous region on earth (4.5 billion) – to 86 million people. India has the highest number at 38 million. The report expects medicinal cannabis consumption alone to increase faster in Asia than in other early-adopter nations and regions.

China and Japan are Asia’s two largest value medicinal cannabis markets – 90% of the Asian market between them – worth almost US$4.4bn and $800 million respectively.

Comment (1)