Lessons from California’s legalisation process were bestowed upon the Cannabis Industry Wales summit in an inspiring speech from John Calcagni, who recently moved from the US state to Cardiff Bay, covering everything from his own battle with mental health and the impact of cannabis during the AIDS epidemic to the ‘Willy Wonka Weed Factories’ that now exist in the form of dispensaries.

John first visited Cardiff in 2013 he fell in love with the the city and ended up receiving his Master of Public Health degree at Cardiff University in 2018. His education and career undoubtedly boost his insights into the cannabis debate – he previously worked on healthcare technology and primary care research for University of Michigan’s Department of Family Medicine, Stanford University Center for Health Policy and Primary Outcomes Research, and the United States Veterans Administration Palo Alto Division.

“Being here puts me in a fairly unique position to provide a broad public health policy overview and a clinical encounter experience of California medical cannabis policy from a first person perspective,” he said. “My background is translational research into clinical support in GP practices. That is a very fancy way of saying how research evidence can be applied to clinical care.”

John said that in between working and receiving his degree, “a lot happened”.

He explained: “I am one of the 47% of adults in Wales who has lived through at least one adverse childhood event (ACES); I’m one of the 14% who has experienced four or more. What happened to me is much less important as how it affects my health. Public Health Wales acknowledges that the stress of ACES worsens health outcomes when those children become adults.

This was an amazing night and an incredibly special moment for me personally. Speaking alongside @UKCannabisClubs @ArfonJ @axelklein2 @vitalityhemp and Neil Anderson with the support of @LeanneWood and @cannabis_wales was a pleasure. I look forward to working together more! https://t.co/6btK61P5ts

— Semikindasortasilurian (@semisilurian) 9 January 2019

“The development of mental health secondary ACES is a little more complicated. What happened to me is that my brain became bad at differentiating between good stress, bad stress and no stress. That manifested as overwhelming panic, starting at age 27. Over a month those panic attacks became continuous runs of terror. This went on and on and I became suicidal from the sheer volume of panic.

“My brain changed in a way we call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). I suffered a laundry list of symptoms. It’s not just psychological. There are demonstrable changes in the body. The lasting neurological changes from the original stress causes the brain and body to re-live that stress. I had to go on disability leave from a great job that I had just started months before. I couldn’t return soon enough and I lost the job.

“That was the beginning of a decade of treatment. As is the case in the US, insurance is a problem. I needed psychotherapy but the insurance I had wouldn’t cover anything but group therapy, which is a bit of an ask for a panicky agoraphobe. Eventually I needed specialty inpatient treatment. The hospital asked for a £6,500 deposit because it had previously had issues with being paid by the insurance company.

“That was the beginning of a decade of treatment. As is the case in the US, insurance is a problem. I needed psychotherapy but the insurance I had wouldn’t cover anything but group therapy, which is a bit of an ask for a panicky agoraphobe. Eventually I needed specialty inpatient treatment. The hospital asked for a £6,500 deposit because it had previously had issues with being paid by the insurance company.

“You know what was covered well? By 2009 I was no longer having panic attacks because I was no longer feeling much of anything. I was an over-sedated, over-medicated zombie. My short-term memory was gone, so psychotherapy had a lot of trouble sticking. I rarely left the house, I couldn’t think straight, I was barely a person anymore. My choice was between numbness or endless panic. There had to be a better way.

“By 2013 I had reduced or eliminated most of what I had been

taking. I was functioning better, I was talking to my friends again. I

went from only leaving the house to see my doctors to travelling again.

Along the way I stopped here. This neighbourhood

is now my home, which is just about the coolest thing ever. So what did

I do to get from 2009 to 2013 and 2013 to now?”

The answer, of course, had something to with cannabis.

John “became part of the experiment” in California. “I found that cannabis calmed me down. It helped me get to sleep, it reduced my nightmares, it helped me interrupt flashbacks, it reduced the side effects from my prescriptions, and helped me function so much better than when I was drugged to the gills.”

But what motivated California to recognise the benefits of cannabis? John turned to 1991 – the height of the AIDS epidemic.

“200,000 Americans had died by the end of 1992. Most were gay men. The lack of coherent public health policies that lingered from the Reagan and Bush administrations from ignorance and prejudice and the disproportionate impact on a minority were catastrophic for the city.”

John showed heatmaps marking the addresses of people who had died from AIDS: “From 6,000 in 1998 to almost 15,000 four years later. Those addresses are concentrated in The Castro, that’s the gay neighbourhood. Imagine losing 9,000 men over the course of four years from one community.

“The drugs that can halt progression and stop transmission wouldn’t hit the market for years. If they couldn’t stop AIDS from killing them, patients and the people who loved them needed a way to hold on until some better drugs came

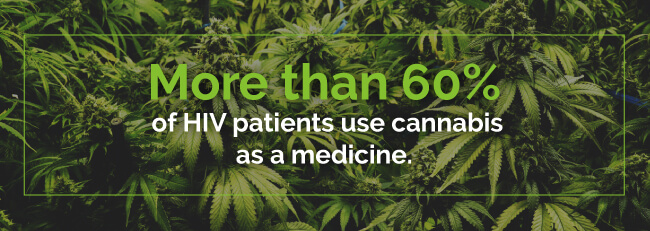

“Cannabis eases pain, it calms you, it gives you the munchies. Less physical and mental stress and more food intake meant a better chance of survival.

“It also meant that they were federal criminals. California saw the value in decriminalisation as early as 1975 but the political environment had changed massively.

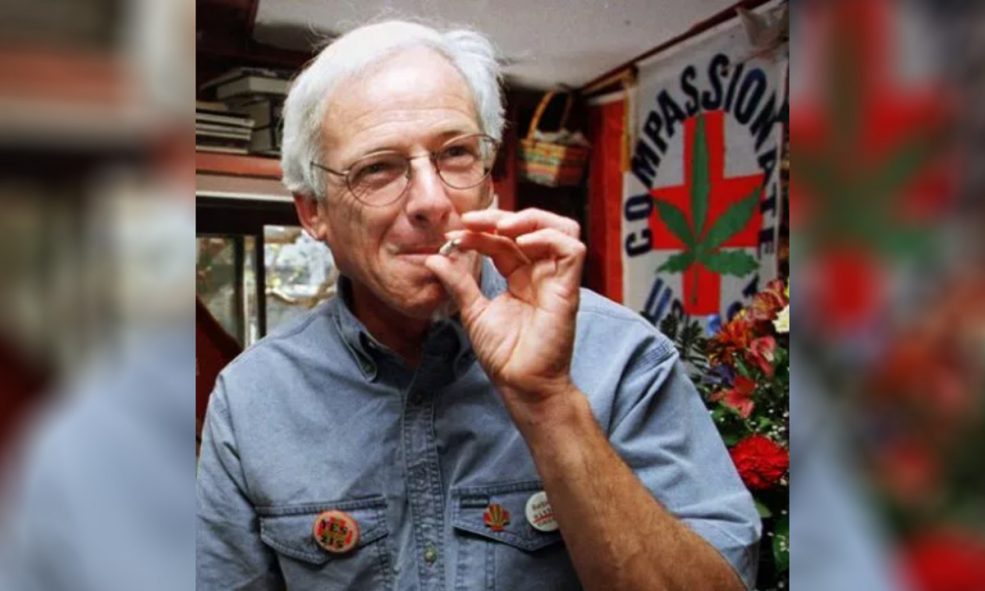

“Brownie Mary, as she’s affectionately referred to, was a sweet little old lady who made hash browns for her dying neighbours. As such, she did not care how many times she was publicly arrested. It was terrible optics for law enforcement.

“Dennis Peron’s partner was dying of AIDS and cannabis helped him, so Mr Peron authored Proposition P. It passed in 1991. Proposition P was mostly symbolic but its wording for the affirmation of the value of cannabis as medicine was a template for Proposition 215.

“The state legislature couldn’t get decriminalisation bills past the conservative governor. But in 1996 we had a presidential election with an incumbent who was popular with progressives. Dennis Peron made sure to get his referendum onto the election ballot and California finally got its medicine.

“The Compassionate Use Act recognised that cannabis has an inclusive and proactive definition of usefulness. AIDS was a horrible surprise that cannabis could help – there were going to be other surprises. The act aimed to support patients and carers from criminal sanction, provide safe and affordable distribution, protect physicians who recommended cannabis, and exempt patients from current drug state law.

“They had to lay down the ground rules. The referendum was just an affirmation senate bill – 420 was the one that defined limits on purchase, possession, cultivation, patient collectives and acceptable use. There was a lot of leeway given however. If patients needed more than eight ounces at a time, they could get an exemption from their GP. It legalised sale but citizen counties didn’t have to licence dispensaries in their area if it didn’t want to. It provided for a state-wide registry but that registry was made voluntary because people were still scared of law enforcement coming after them.

“People preferred to register with private verification registries, but that makes uptake of the medical cannabis programme difficult to estimate. The estimates from California are based on data taken from Maine. They indicate that about one in 30 people had a medical recommendation by 2016, that’s 1.3 million in California.”

Recreational decriminalisation passed in California in 2016 and sales began in January 2018.

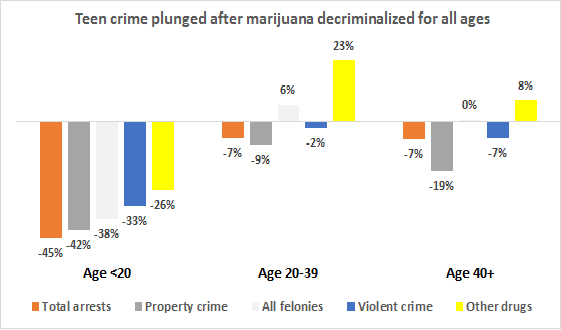

On the law enforcement front, cannabis-related arrests fell away, and drug overdose deaths, high school dropouts, cannabis intoxicated drug offences and property crime, all dropped significantly more in California for those aged 15-19 than for the rest of the US.

However, doctors who recommended cannabis were sanctioned by the federal state medical board and President Bush stepped up raids of patients and dispensaries. It wasn’t until 2009, 13 years after the referendum passed that the Presidency, under the Obama administration, publicly stated that it would stop making patients criminals.

“Medical cannabis took off in California that year. I finally felt safe enough to use cannabis without ending up in jail,” said John.

“But new laws did not protect people equally. There had been racist messaging behind prohibition. The ‘Reefer Madness’ propaganda from the first half of the 20th century emphasises foreigness and non-whiteness along with promiscuity and danger. To this day African-Americans are five times more likely to be arrested for possession.

“There are also huge financial barriers to access. It looks very simple: get the card, get the cannabis, use the cannabis. But to get a recommendation you needed to have an actual examination by an actual doctor. It’s still federally illegal to prescribe cannabis because it’s a scheduled substance. Most people’s GPs and specialists were still very wary of giving recommendations. State-wide corporate practices sprung up to fill that healthcare niche by allowing doctors who wanted to provide recommendations – not prescriptions – diffusing potential liability and the workload.

“These same practices held and operated patient verification registries. Patients were given paper copies of recommendations valid for one year, a licence to grow at home, and a card with portable verification information.

“Doctors who gave recommendations also gave harm reduction education on the safest ways to use cannabis and the limits on when and where you could use it. But all this was costly. These practices were private – the likes of veterans received discounts, but that sort of means-testing was never a given. Entry costs were $100-$200 just for the first appointment.

“Dispensaries were hard to get to in 2009. The first one I went to was 35 miles away. By 2016 it was a 10-minute drive. They weren’t always in the nicest of areas because cities could often zone them into industrial areas or out-of-the-way store fronts. Private security was very tight and there was usually some police presence nearby.

“Despite the zoning restrictions there was no association between the density of dispensaries and violence or property damage. As these dispensaries were usually operated as co-operatives you had to register again with them to designate them as a care-giver or to become part of the patient co-operative

“Dispensaries referred to product prices as suggested donations, so as to avoid direct payment for cannabis, still prohibited under federal law.

“Inside, you were faced with Willy Wonka’s Weed Factory: concentrates, capsules, butter, really good cookies made from that butter, boiled sweets, drinks, lotions, 10 to 40 different strains of flower, three kinds of vaporisers and a rooms full of plant clones.

“The people working in them were often medical cannabis patients themselves. They were generally knowledgeable of the needs of patients like me who were completely bewildered.

“The strains were labelled with the ratio of THC to CBD as a rough guide to their effect. High THC and high CBD both have their utility. I needed something that would help me sleep and calm me down but not make me feel tired or jittery and I got it wrong a few times. There’s a strain called Romulen named after the paranoid, angry aliens in Star Trek, which I think is completely apt, but someone else might find it really good for pain and inflammation. One size just doesn’t fit all.”

But all of it would be called Skunk here, said John, who had had never heard the term before moving here.

“The UK is not doing something special to grow specifically medical cannabis instead of the dreaded Skunk,” he said. “The cannabis you get in the dispensary is the same as you get from illicit dealers – aside from being much safer, from a more ethical supply chain and being much better quality.

Powerful stuff from @semisilurian such an inspirational and moving talk. If anyone wants to hear about the havoc wreaked by prohibition then talk to this man! Thank you ? pic.twitter.com/LEwOSGT0B3

— Cannabis Industry Wales (@cannabis_wales) 8 January 2019

“You also get harm reduction info at the dispensary. You are instructed to take your sealed bag of medicine, put it straight in the boot of your car and not to hand it to anyone else, or you’d be banned from purchasing.

“The costs remain slightly lower than street costs. It was still a lot of money per flower but the cost of other products was much more variable. Again, there was some discounting and means-testing but that still wasn’t guaranteed.

“Eating cannabis doesn’t work well for me. It takes a while to kick in, which isn’t great for panic attacks, and the effects last a little longer than I need them to. I vaporise so I can tightly control the effects but how you use is another barrier to safe access and equitable outcomes. It’s far more unhealthy to smoke but it’s much cheaper than buying a vaporiser or the equivalent edibles or capsules. Crowd-sourced data is the best way to find out the effects of each strain.

“The end-to-end costs for an examination to getting the cannabis home is quite high. This is a huge barrier to entry. I was lucky enough to be able to afford those costs.”

To loud applause, John added: “This is what I did. Cannabis changed my life. I am now standing here in the Sennad.

“Unlike Skunk, California is not a myth, and neither is good cannabis policy. The spectres of increases in psychosis, crime and violence have just not materialised. It’s safe and effective there and it can be safe and effective here. Devolution in the current political climate could put Wales in a very unique position.

“The only advice that I have, is not to wait for an emergent public health crisis and a five-figure body count to do something. Cannabis decriminalisation and regulation is no longer an experiment, the experiment is long done.

“There is good public policy precedent in California, Alaska, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Marilyn, Mississippi, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Australia, Puerto Rico, Poland, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Macedonia, Turkey, Uruguay, Spain, Portugal, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Jamaica and Chile. Why not here?”