Portugal may be well known for its decriminalisation model that treats drug use as a health rather than criminal issue, but it has passed up the chance to seal its reputation as a bastion of progress after politicians voted down an attempt to legalise the cultivation and sale of cannabis for recreational purposes.

Two proposals were put forward. The first, by the People-Animal-Nature party (PAN), suggested limiting individuals to buying 75 grams of cannabis per month from licensed pharmacies, where sales would be overseen by state health agents who would provide information on the drug and its risks. It also promoted the right to grow six plants of cannabis per household.

The second proposal, from the Left Block, advocated a more relaxed approach, permitting the sale of cannabis at any licensed establishment. It also would have permitted home cultivation.

Both wanted cannabis to be regulated at a price equal to or lower than that of the illegal market and both prohibited the advertising of cannabis products (a placation ploy that evidently didn’t work), with restricted to Portuguese citizens or residents over 18 who do not have mental illnesses

Jamila Madeira, a legislator of the ruling so-called Socialist Party (PS) opposed the proposals, saying that while legalisation might perhaps be a “natural evolution”, there were too many unanswered questions on how to monitor consumption and the effects of cannabis use on young people. She claimed there would be no way to ensure there was no “proliferation of psychosis”.

Public opinion is also fairly split, with a 2018 survey putting opposition to legalisation at 53% of the population, with a clear divide in views between metropolitan and rural areas.

According to Talking Drugs, the consensus among many government authorities is that cannabis legalisation may be the right path to take but “officials want to see long-term positive results from Uruguay or Canada before making legislative change. US approaches are not seen as desirable in Portugal, according to the national drug coordinator João Goulão, partly because of perceived American prioritisation of business over health.”

At least prescription cannabis-based medicines (although not herbal cannabis) became legal in February, following passed legislation in June last year. Previously, only Sativex had been available, since 2012, but its use has been minimal “due to the stigma associated with cannabinoids, cannabis’ blurry legal status, and crucially, due to its exorbitant cost that is not covered by national health insurance”.

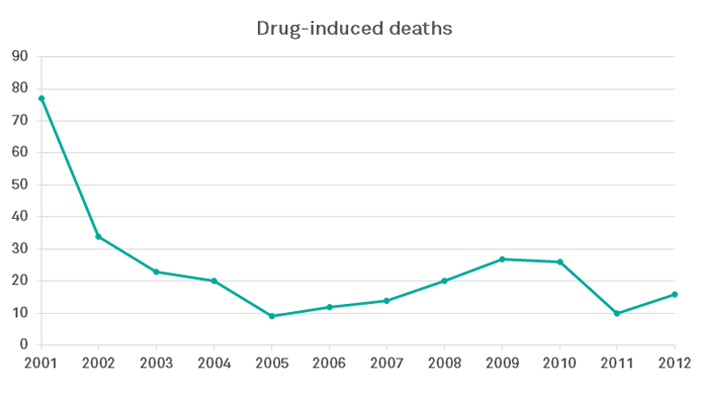

Since 2001, all drug use has been treated as a health issue in Portugal. Drug possession was decriminalised, so anyone caught with small amounts of drugs for their own use has since been referred to be offered education, treatment options, or other social supports.

The policy was introduced to address the country’s heroin epidemic, which was the worst in Europe. In those 18 years Portugal has experienced an overall reduction in drug use, a consistent reduction in drug use by young people, and a massive reduction in both overdose deaths and HIV infection rates for intravenous users. Thanks to the holistic support which complemented the law change – the abundance of treatment options, cultural education, and re-integration of addicts back into a productive life – the policy has been a resounding success.

But decriminalisation to some extent reinforces stigma by automatically assuming users need help. And, of course, it does not address the supply side, which leaves the black market free to sell polluted, harmful, bad quality drugs in the first place.

Comment (1)